In economics 101, you learn about consumer surplus, producer surplus, and social surplus. For those of you unfamiliar with the concept, you can think about it in terms of when you go shopping and you see something you know you shouldn’t buy and you tell yourself “Okay if it’s less than X dollars, I’ll get it, but if not, I won’t.” That X, be it $5 or $50, is, in economic terms, your marginal benefit. Essentially, by setting that price point for yourself, you are implicitly saying that you think you will get X dollars worth of benefit from that good or service. The “marginal” comes in, because it is your benefit on the margin. So the benefit you get from owning one additional unit of that good or service. A demand curve plots the marginal benefit for different units. That is a slightly less concrete concept, because, for any given specific good, you usually get a certain amount of marginal benefit from buying it, and then you get no additional marginal benefit, or at least very little, from owning say two identical t-shirts or two copies of the same video game. But, you can think of it in a lot of different ways. First of all, you can think of it as a more aggregate concept. You get a lot of benefit from your first video game, and then another one gives you some additional benefit because you like variety, but not quite as much as the first game because the first game is the difference between having something to play and nothing to play at all; for clothing, even though our price point for shirts might depend on the specific shirt, in general you can aggregate them and think of how much you’re willing to spend on a first shirt as how much benefit you get from not having to go topless and each additional shirt as how much benefit you get from an extra day putting off doing laundry. That is just for your personal demand curve. The market demand curve, which is the sum of all of the demand curves in the market, is essentially how many goods you will sell to the population at a particular price point.

On a tangential note, I gave a lecture yesterday and now I keep having the instinct to add in “does that make sense?” which would, of course, make no sense to do (see what I did there?). But this seems like a good time to tell you that if you ever don’t understand what I’m saying, feel free to leave a comment!

Anyway, that’s demand, or marginal benefit. Supply is marginal cost, or how much it costs to produce an additional unit. You can think of that like when you are haggling with someone and you reach the lowest possible price that they were willing to sell for. So, if you say that you would have spent $X on something (lets say 10), and it turns out to cost $8, then you are paying $8 dollars on $10 worth of benefits. Look at you champ! You just got two dollars of consumer surplus!

If you buy something at a street fair for $10 because the person at the booth had that no-nonsense-not-a-chance-I-haggle face, but they totally would have sold it to you for $8, they have now gained $2 of producer surplus, and the personal satisfaction of thinking “suckerrrr” as you walk away.

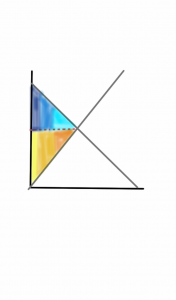

If you look at the chart below, if the good is priced at equilibrium, social surplus (or the sum of producer and consumer surplus) is maximized.

The consumer surplus is the sum of the difference between the price and all of the buyers in the dark blue section, which is what they would have paid minus the equilibrium price, plus the slightly smaller medium blue section, plus the even smaller surplus for those in the light blue section, who would only be willing to pay a slightly higher price than the current price point. The surplus of each individual buyer makes up the consumer surplus total, and is represented by the area under the demand curve up until the price point, or the triangle formed between the price point, the quantity, and the Y intercept of the demand curve. Producer surplus works in the same way. The group of suppliers in yellow would be willing to sell for a lower price so they get the surplus between that price and the equilibrium price, and so on and so forth. Producer surplus is the area above the supply curve up until the price point, or the triangle formed by the price, the quantity, and the Y intercept of the supply curve.

When a monopoly sets their price at the profit maximizing point, as you can see, the producer surplus increases drastically while the consumer surplus becomes itty bitty.

The gray area you see is deadweight loss. A certain number of goods are being sold at a certain price point. If the price point were lower, more goods would be sold, and the surplus created by that would be greater than the surplus created by the monopoly situation. The surplus that we do not get is known as deadweight loss, and is represented by the gray area. Even though social surplus has shrunk, producer surplus has increased; the monopoly price maximizes producer surplus at the expense of consumer and overall surplus. This is known as allocative inefficiency.