This season’s Big Bad

I watch a lot of DC Comics TV shows, so sorry if the whole ‘big bad’ framework is too nerdy for you. That said, you are spending what is presumably your free time reading an economics blog and I have never pretended not to be nerdy.

Monopoly and Monopsony

How many companies do you think would wish they were big if they encountered Zoltar? (For those of you who have no idea what I’m referencing, it’s a 1988 movie called Big starring Tom Hanks and you should definitely watch it). Here’s the problem: a big company has market power. Market power, by simple economic definition is how much capacity a firm has to drive prices, but the concerns go far, far beyond that.

First and foremost, market power causes market inefficiency and deadweight loss, as well as redistributing surplus from producers to consumers. For those of you who don’t know, or need a refresher, on deadweight loss and consumer and producer surplus, check out this post.

Even though monopolies are not ideal, if a luxury good is produced by a monopoly, that’s not such a huge deal, at least in terms of social impacts. However, one of the most common industries for monopolies, if not the single most common, is pharmaceuticals because they are granted patents. I’m not saying that patents are inherently a bad thing; astronomical amounts of money go into the creation and testing of new drugs. I worked in branding last year and you’d be surprised how hard it is to even name a new medication (if the name is too similar visually or aurally to something on the market, dangerous medication errors can occur).

If we didn’t grant patents there would be no incentive to put in the research and development money if someone else could just use the formula as soon as you finished it. While some policy makers are seeking alternatives to incentivizing R&D, patents remain the prevailing strategy for the time being. So, yay R&D! Except, remember that time a guy who would later be referred to as the “most hated man in America” raised the prices on an AIDS medication from $13.50 to $750 a tablet. Nobody can sell that drug for cheaper, so anyone who needs that medication needs to pay up or face major health risks.

A company doesn’t have to have full-blown monopoly power to have a dangerous level of market power. The more market power a firm has, the harder it is for other, smaller firms to compete.

Another major issue with huge companies is monopsony power, which by economic definition is a company that is not facing competition for the purchase of inputs (where labor is an input to be purchased) (to be clear when economists talk about purchasing labor, they mean purchasing a service from the “seller” who is the individual worker). Often, monopsony denotes a firm that is a single employer for an area or group (though it can also denote a firm that is the only client of a given capital producer). Again, even if a company does not literally employ every single person in an area, they can still have dangerous market power. Just like a monopoly prevents consumers from seeking a better price or product elsewhere, a monopsony prevents workers from seeking a better job or salary elsewhere. As I mentioned in my post on inflation, one issue caused by sticky wages is the continual redistribution of income to profit-earners instead of wage earners. In October 2016, the Council of Economic Advisors released a brief on monopsony power, with one key argument that monopsony is helping to drive such redistribution. The brief also points out that, as monopoly power drives prices upward while driving quantity downward (thereby productivity and creating that deadweight loss), monopsony power drives wages downward and number of workers hired downward. In terms of social impact, we not only have larger unemployment, with even those who are employed making a lower wage than is optimal, which can slow down economic growth in a number of ways, we also have lower output. Going back to the very basics of supply and demand, less output means a higher price for consumers. Also, the impacts of inequality pose major issues to economic efficiency, a subject I could easily dedicate an entire—or several entire—posts to discussing.

The issue of incredibly powerful firms goes well beyond the traditional goods and service markets or labor market impacts of standard theory and discussion. The issues posed by Amazon, which The Seattle Times says has turned Seattle into “America’s largest company town,” have little to do with their power over their employees. Amazon workers, who are typically high skilled, high paid workers, are not necessarily the ones suffering. “What was once a quirkily mellow, solidly middle-class city now feels like a stressed-out, two-tier town with a thin layer of wealthy young techies atop a base of anxious wage workers,” Paul Roberts writes for Politico. Seattle also is experiencing overwhelming traffic problems and major rise in housing prices.

To be clear, I’m really not trying to make Amazon the villain. I am not convinced that I would have survived this long without my Prime account, and the ability Amazon has given me to be both lazy and cheap at the same time is truly a gift. But Amazon is still a for-profit company, and they are going to do what they can within the bounds of ethics and a degree of corporate social responsibility to have the highest possible bottom line. Even assuming total benevolence on the part of the monopsony too large a corporate footprint puts too many eggs in one basket. In fact, Seattle had that exact problem in the 1970s when Boeing was the single dominating force. As a New York Times writer describes it, some “worry that the city could become too much of a one-company town, the way it felt in the old days when Boeing would sneeze and the city would pull up the blankets and stay in bed.” I’m not even going to consider the post-apocalyptic nightmare of a Prime-less world, but, even if Amazon, like Boeing, takes a hit but lives to tell the tale, Seattle could still be in major trouble.

Monopsony companies also have undue power over governments, which is really scary when you think about it. The issue isn’t just employment: Amazon owns 19% of Seattle’s office space. That’s as much as the next 43 companies combined. To be clear, that’s also the next 43 largest companies, so Seattle wouldn’t just have to bring in any 43 new businesses to make up for a loss of Amazon. Seattle is also undergoing major public works projects to deal with the new found traffic problems caused by Amazon. More people means a larger taxable base: if you lose that population you’re now paying for a project with money you don’t have for people who aren’t there.

The resulting power manifests itself, in the case of Amazon, through cities bidding to be the home of HQ2, or Amazon’s second headquarters (a dubious blessing according to Seattle, but certainly an in demand one). A New York Times article basically describes the “wooing” of Amazon as an exercise in Peacocking by cities (238 of them, to be exact). Your taxpayer dollars are hard at work funding a viral video of the Mayor of DC talking to Alexa, the transportation of a 21 foot tall cactus 1,538.9 miles (thanks google maps!) via flatbed truck, from Tuscon to Seattle, and ads from the city of Calgary promising to fight a bear to get Amazon’s headquarters (I am at present unclear as to who exactly will be fighting the bear, whether any actual bears will be harmed in the courting of this company, and if so what animal rights group I should contact). Yes, that’s right, you heard it here first, forget habitat destruction and global warming, monopsony companies are what’s really hurting our wildlife.

Joking aside, Amazon has requested that each city include in their application tax breaks and incentives that the city would provide. My own home state of New Jersey offered a 7 billion dollar tax cut to get Amazon into Newark. I’m already a little concerned at that prospect, honestly, because I’m thinking I’m going to start flying into the airports in New York City proper, because the traffic to get home from Newark Airport is going to be insane. Of course, that’s totally speculative on my part, but if Seattle is any indicator, the line of thinking is at least legitimate.

All of that being said, Amazon is not the most concerning example of monopsony, it’s just relevant given the recent news surrounding the company. Where monopsony poses a huge threat is in developing countries. I do want to start by saying that I am focusing on the concerns about monopsony, but having large companies invest in a developing area has advantages, including but not limited to employing impoverished populations, increasing inflows of capital and expertise, fueling growth. The problem is that a company large enough to bring with it huge benefits has huge power, and that is always going to pose risks.

The way I normally think of the issue of monopsony in a developing region is through a game theoretical model, which a lot of you are probably familiar with, called the prisoner’s dilemma.

Suppose the UN passes a resolution on environmental standards, work conditions, tax levels, and wage levels, and recommends that all countries abide by those standards. Simplifying the model to two countries, suppose each one of them has to decide whether to follow those guidelines or not. The prisoner’s dilemma model can apply to any situation in which a binding legal agreement is not possible. Because of issues of national sovereignty, even if every nation agreed to the guidelines (which we must assume for the model to be relevant at all), they are extremely difficult to totally enforce (I did Model UN for years in high school and first of all, TNCs or transnational corporations with monopoly power were a topic all the time and second of all the words national sovereignty were thrown around so much that I am just glad I wasn’t 21 yet because turning it into a drinking game might have killed me).

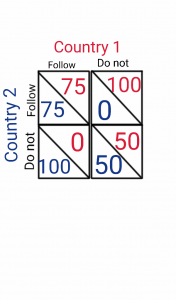

In this model, you have country one and country two. If both countries stick to the guidelines, then the monopsony corporations will split evenly between the two, and they will both get a payoff of 75, giving a total payoff of 150. If one country does not follow the guidelines, however, and makes doing business in their nation cheaper, the business will flock to their country. They will get a higher payoff, and the country that did follow the guidelines will get nothing. If both countries choose not to follow the guidelines they both only receive a payoff of 50. They still get the benefits associated with the monopsony presence, but they get less because they are unable to regulate at the optimal level. Unfortunately, at least according to the theory, that 50,50 point is the outcome we get.

If country 1 knows that country 2 will follow the guidelines, they stand to make more by ignoring the guidelines. If country 1 knows that country 2 will not follow the guidelines, then if they follow the guidelines they will get nothing. So not following the guidelines is what is called a dominant strategy. Basically, no matter what the other player does, your best option would be to do the same thing. Now lets step back again and think of this in terms of 20 or 30 nations and all of them have to agree totally, and things get even more complicated. How, exactly, now, do we try to enforce emissions standards and living wages. Many efforts to rectify the issue would require giving conglomerating power, which makes them dubious strategies for a problem caused by high concentrations of power.

Big Names in Economics (And Big Feuds)

Read this section if: A) you have already read through Elle Magazine’s 65 page article on everyone who Taylor Swift is feuding/has feuded with and you are looking for a new source of drama (that page count is including ads, but still), B) you, like me, didn’t even have time to get through the list of female artists she’s feuded with but still need a celebrity feud fix, or C) aren’t reading an economics blog because of the celebrity gossip and are just interested in the ideas(I mean, if you say so).

Amazon vs. Walmart

Okay, so I initially was going to write this section only about theorists and philosophers, but I really do live for the drama and the billion dollar cat-fights. When Amazon announced that it was accepting bids, a business group in Little Rock, Arkansas (proud home of Walmart) made a video and took out an ad in the Washington Post, which is owned by Amazon’s CEO, to say that they didn’t want to deal with the traffic problems Amazon would cause. The ad reads like a break up letter from that one ex you have who really thought they were hiding the fact that they thought they were better than you. These, my friends, are the lifestyles of the rich and famous. One day we too can aspire to have the money to be petty in such an expensive manner. (To be clear, I would absolutely high five the people who did this; I never said petty was always bad).

Rawls and Nozick

John Rawls and Robert Nozick pretty much go hand in hand in the cannon of political philosophy; the opening line of an encyclopedia entry on Nozick is as follows: “A thinker with wide-ranging interests, Robert Nozick was one of the most important and influential political philosophers, along with John Rawls, in the Anglo-American analytic tradition.” Of course, by hand in hand I mean they went to totally opposite ends of the spectrum. Interestingly, Rawls is mentioned in the second sentence of a different encyclopedia entry on Nozick as well, but Nozick is barely a footnote in both entries on Rawls. Nozick’s name pops up as a critic or a counterpart to Rawls’ work exclusively.

Nozick is best known for his theory of Anarchy, State, and Utopia, and his theory centers around the principle that all people have a right to self-ownership. A person’s rights must be respected above all else, particularly the rights to life, liberty, and the fruits of one’s labor. His argument then is that state intervention is an infringement of rights, in particular redistributive taxation amounts to forcing labor by taking away part of the fruits. He doesn’t advocate for total anarchy, but instead a “night watchman” state, which forms essentially to perform only the regulatory needs that allow for the protection of rights (i.e. police).

Rawls on the other hand, has an utterly opposite principle, that a society should be structured in such a way that rather than prioritizing rights above all else, it prioritizes having the highest possible utility for the least well off of society, even if that means less overall social welfare.

Three key factors make up his argument, his principles of Justice as Fairness and the concept of the veil of ignorance, which is something of a thought experiment.

The principles of justice are described as follows by the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

“First Principle: Each person has the same indefeasible claim to a fully adequate scheme of equal basic liberties, which scheme is compatible with the same scheme of liberties for all;

Second Principle: Social and economic inequalities are to satisfy two conditions:

- They are to be attached to offices and positions open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity;

They are to be to the greatest benefit of the least-advantaged members of society (the difference principle). (JF, 42–43)”

The veil of ignorance essentially says that we should strive for the society that we would want if we had no idea what position we would be born into (race, class, gender, nation, etc). In that way, we would want to make sure that even the lowest possible outcome is still a good option.

The two theories are totally mutually exclusive, as the “difference principle” mentioned in the encyclopedia entry demands income distribution, and focuses on society as a whole, while the Nozick model is totally driven by the welfare of the individual. That said, interestingly, both hold an ideal, be it fairness or selfhood, above optimizing social surplus. When we think of how many economic models focus on efficiency, thinking about, whether or not you agree with either of these two in the slightest, what else we might prioritize is important.

I also want to take a more serious note on the whole feuding aspect of these two to think about what it tells us about partisanship. These two have deep-rooted, fundamental beliefs that utterly oppose one another. When we look at the state of politics right now, I have no idea how to deal with the amount of partisanship we have (talk about inefficiency). I think, maybe, we have to start with figuring out what universal priorities we hold as a nation. I have to believe we have some, because otherwise we would all be hopeless. I also think looking at these two is a lesson in choosing your battles. Sometimes when we argue about politics, with family, on the internet, wherever it may be, it is an issue of someone being categorically, factually wrong. Sometimes, though, we just have to accept the fact that other people are fundamentally different from us and maybe consider the fact that they may not be totally awful because of it. Okay, I think that speech sufficiently balanced out the fact that I took so much joy in pettiness, so I’ll leave off there.